The word “identity” constantly appears when it comes to national issues, but in fact it applies to almost all areas of human knowledge. Whether this term fights conservative politics, how hybrid identities are changing pop culture and why a person’s status requires proof was discussed by Mark Simon, teacher of the master’s program “International Politics” at the Moscow Higher School of Economics and Social Sciences, and Daniil Aronson, a researcher at the Institute of Philosophy of the Russian Academy of Sciences, at a discussion organized by the Jewish Museum and the Science project .me. T&P covered the main points.

“Identity” in politics and analytics

Mark Simon: In everyday life, the meaning of the term “identity” seems to be beyond doubt: everyone should have some kind of identity. However, there are two ways to use this concept.

The first is the language of political practice, in which it has been used since about the mid-1990s. When politicians talk about identity, their task is to convince that each group they address has a special commonality and solidarity, and internal differences do not matter.

The second is the language of theory. But when we try to understand what this word explains to us about social or political relations, it turns out that it is very semantically overloaded. American sociologist Rogers Brubaker has an important article “Beyond Identity” (it was included in the collection of his works “Ethnicity without Groups”). Brubaker says that the term “identity” itself began to figure prominently in the language of social theory in the United States in the 1960s and from there came into politics. As a result, analytical and everyday languages become virtually indistinguishable. But in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the struggle for “identity” began: several works appeared in which this concept was rethought.

Brubaker believes that there are two groups of interpretations of “identity.” One can be called rigid, or essentialist (from the English essence - “essence”): it is assumed that each person’s identity is predetermined, inherent to him initially as a representative of a certain group, even if he is not aware of it. It seems to me that this approach dominates in Russian political language.

In our country, national identity presupposes that a person acts in a certain way due to his ethnocultural essence.

Brubaker calls the second group of interpretations soft, or constructivist; this language of speaking about identity was formed by the 1990s. According to such approaches, a person lives in some new social and information space, belongs to many social worlds, and depending on the context, his idea of himself is constantly being transformed. Identity is something fluid, flexible, plastic, elusive - a certain set of categories, a language that does not reflect what a person already has, but works in a performative manner. A person initially does not think that he has any identity, but by accepting a certain language, he begins to become aware of himself in a certain way.

© stocksnapper

Loss of identity

“I’ve lost myself”, “I don’t know who I am”, “I’m confused in myself”, “I don’t know where I’m going, what I want” - these are the thoughts that come to a person who has lost his identity. A person loses faith in himself, understanding of his place in the world, the integrity of his Self. An exaggerated example of loss of identity is mentally ill people who consider themselves Napoleons, Jesus, etc. This example belongs to the pathological extreme; psychiatry deals with them. We'll talk about what psychologists work with.

Causes

Causes of loss of identity (personal crisis):

- drastic changes in society (for example, many people faced this problem when the USSR collapsed);

- serious and unfavorable changes in the life of the person himself (dismissal, bankruptcy, divorce, someone’s death);

- age crisis, for example, midlife crisis.

In general, the cause of loss of personal identity is stress. Moreover, this can be both an unpleasant experience and a very pleasant one. For example, a wedding, a long-awaited move to another country, or the birth of a child can also cause a loss of identity. This occurs due to any strong psychological shock.

Symptoms and signs

Symptoms of loss of identity:

- frequent doubts such as “Why don’t I leave this job?”, “What am I doing here?”, “Why am I living with this person?”;

- constant reflection on the meaning of life and purpose;

- feeling of uncertainty;

- frustration;

- chronic anxiety;

- inability to form a system of values and stable beliefs;

- doubts about the correctness of your actions;

- fear of the future;

- indecisiveness in actions.

For some people, the crisis is visible to the naked eye. They spend their time aimlessly, wander, they do not have a job or they change it often, or they are stuck in one position (usually a low one). Some people can't even get an education. Some people end up in bad company, some end up in prison. But most people just exist. They are unhappy, they do not understand what they want and what they can, where they need to move. In general, a person in such a state does not know who he is, and therefore cannot be himself and suffers greatly from this.

Danger of condition

How dangerous is this condition:

- exhaustion,

- maladjustment,

- desocialization,

- insulation,

- depression,

- neuroses,

- suicide,

- dependencies.

Some people try to console themselves with alcohol, drugs, or casual sex. Someone begins to grab onto everything in a row (any type of activity), but this only increases the feeling of emptiness and frustration. Others simply become depressed and lock themselves at home, waiting for death.

What to do

Remember where you last saw yourself. Try to remember a time when you felt good. What kind of person were you at that moment, where were you, who was nearby. Start with an analysis of childhood and gradually move towards the present. Remember what you could do, what you dreamed of, what you wanted. Why did they refuse this? Maybe it's time to return to this again? Think about what used to bring you joy, what was the meaning of life, an incentive. If you can't bring back exactly this, then think about something you can replace that is similar to this.

Thus, you need to find the reason (what brought you down) and work with this area. It is necessary to go through all stages of development again, starting from childhood. It's better to consult a specialist. In some cases, just one consultation is enough.

Identification vs. identity

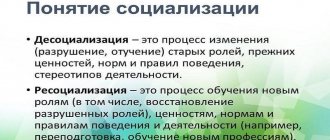

Mark Simon: According to Brubaker, the problem is that even if we use a soft interpretation, it is still unclear what we learn from the concept of “identity.” He suggests finding a different, more nuanced theoretical language. He puts forward the concept of “identification,” which comes from psychology and was used in the social sciences before “identity.”

Identification, a verbal noun that implies a process, says that identity is not a ready-made entity, but something that is born in the interaction between people. Identification allows us to trace how certain identities crystallize and take on flesh.

The state likes to categorize the population according to nationality, race and gender. Brubaker proposes to analyze this process and the reaction of citizens to such division. Are these categories always neutral? In what cases do they acquire a negative meaning? When do people not agree to enter the category that the state offers them? The researcher believes that there will always be groups that will offer a different categorization system instead of the dominant one - this is the essence of the political process. When in the United States the concept of “blacks” for obvious reasons carried negative connotations, in the 1960s they tried to redefine it by inventing the “Black is beautiful” movement.

Brubaker offers a number of other terms (including “self-understanding” and “self-presentation”) that show that identification is not simply a matter of relating oneself to different groups. It is social and political in nature, rooted in practices. He is very convincing, but for some reason today most researchers do not abandon the concept of “identity”. Probably, despite all the problems, the word retains a heuristic meaning.

Daniil Aronson: It seems to me that there is a fairly simple explanation for this. The term “identification” cannot replace the term “identity”; it only complements it. If identification is a process that is carried out by bureaucratic forces or some other institutions, then what do these institutions produce as a result of this process? Just identity.

Identity and Identification: What's the Difference?

In short and in simple words, identification is the process of a person identifying himself with a group, imitation of it, the desire to conform, and identity is the result of identification, a person’s idea of himself as a member of a group. Sometimes, even quite often, these concepts are used as synonyms. However, from a psychological point of view, this is wrong. As Erikson noted, identity (result) begins where identification (process) ends.

What is identity politics

Daniil Aronson: The good thing about the term “identity” is that it exposes itself a little. When we talk about identity, we already mean the result of a certain social process. If we want to combat essentialist political doctrines such as racism or nationalism, we need a language that is much more difficult to deal with notions of “naturalness.” When we say that besides sex there is gender, and gender is a socially constructed identity, then the word “identity” acts as a magic wand that clears away the fog of imaginary essentialism. Therefore, among the spheres to which the word “identity” extends, one can single out a progressive politics, which does not proceed from the fact that there are some natural givens and certain political measures automatically follow from them.

We can debate as much as we want about the biological reasons why men are, on average, taller or stronger than women. But as soon as we claim that a certain policy follows from this, we are already using the words “men” and “women” as identities.

When we say that a fact is socially significant, it moves into another field where things are constructed through social rituals, institutions or processes.

As an example, I will take the word “person” - it seems that it cannot be designated as an identity, that it is an ultimate concept. We are all human, this is self-evident, and no politics follows from this. In fact, this concept also often acts as a socially constructed identity.

In 1948, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was released, which outlines the rights inherent in all people. It states that everyone has the right to asylum in other countries if they are persecuted in their homeland. The declaration does not say a word about how exactly this right is implemented - this is spelled out in other international legal documents (for example, in the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, adopted three years later).

During the final years of the Gaddafi regime, the European Union tried to work with the Libyan government to keep refugees from Africa where possible in order to control their flow to Europe. But Libya at that time had not signed the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, and people who found themselves there were unable to apply for asylum. Essentially, they failed to perform acts by which modern law could define them as human beings.

Identity politics is when minorities fight not for their rights, but for the emergence of social procedures and institutions that would allow them to identify in a different way.

A rough example: women are not those who stand at the stove and prepare borscht, but those who have autonomous control over their bodies and can vote.

© ia_64

Types of identities

Some researchers divide the entire set of identities into natural ones, which do not require organized participation in their reproduction, and artificial ones, which constantly require organized maintenance. The first include such identities as racial, ethnic, global, territorial (landscape), and species. The second category includes such identities as professional, national, confessional, contractual, (sub)continental, regional, class, estate, group, zodiac, stratification. Some identities are mixed, for example gender.

Problems of multiculturalism

Marc Simon: Political liberals in the late 1980s and early 1990s believed that rights should be neutral in relation to gender, culture, etc. - that is, equality should not depend on identities. But debate in normative political theory has shown that such neutrality is impossible, and various scholars have argued that we cannot be insensitive to many requests for recognition. For example, in the case of the American Indians, who were oppressed and for whom acceptance as a distinct group is of fundamental value. But progressive measures in this area also entail new problems.

In Canada, the Multiculturalism Act was passed in 1971. It turned out that if we give Indian closed communities some autonomy and the opportunity to determine for themselves who they are, this does not mean at all that such a situation will give rise to further tolerance. Women's rights may not be respected in these communities; these communities may be closed to outsiders and mixed marriages.

When we try to make a progressive gesture and assign individuals to an identity, give them rights or privileges according to that identity, we deprive them of autonomy.

Use in economics

- Brand Identity is the distinctive features of a brand, its individuality (Brand Personality).

- Destination brand identity is a visual concept that expresses the main features of cities, countries, regions and different territories. Territorial identity and national identity are associated with concepts from related sciences. Territory brand management (destination-brand management) is a new direction in brand management.

- Corporate identity - (English Сorporate Identity), expressed in the attributes of corporate style (English Сorporate style). Same as brand identity, but in relation to a corporate brand.

Hyphenated identity

Mark Simon: The concept of identity is derived from culture. Representative of cultural studies and postcolonial theorist Paul Gilroy believes that there are two ideas about culture: the first perceives culture as something static and holistic, the second - as a kind of bricolage, a dynamic phenomenon that often turns out to be cobbled together from fragments of completely different phenomena.

In discussions of migrants in the 1970s and 1980s, the concept of “identity crisis” was often used, implying that a person had become separated from one community, did not fit into another, and found himself somewhere in between. In the 1990s, this concept was replaced by “hybridity”—belonging to several worlds at once. In English there is a term “hyphenated identity” - “identity through a hyphen”: African American, British Afro-Caribbean, German Turk.

Rhizome

A way of organizing integrity that abolishes strict structure, hierarchy and linearity.

Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari compare the rhizome to a tangled rhizome without a main root. The word "rhizome" is also often used to describe the horizontal structure of the Internet. What is "black culture"? Who owns hip-hop? This begs the trivial answer: this is an American phenomenon. But hip-hop was originally Jamaican-influenced, influenced by New Orleans music, which in turn was influenced by West African culture. This is an endlessly circulating system, a collision of different flows - a rhizome.

Gilroy says black culture is a distinct physicality that resists colonial power. In anthropology, this situation is designated by the concept of “liminality” - this is a situation when you are taken out of context and are not recognized as an equal. In this sense, black culture absorbs elements of the European tradition, but provides a specific response to the situation of exclusion.

This double consciousness is practically a schizophrenic situation: you are an African American, but you are always ashamed of the white man who sits inside you and looks at you as an Other.

In talking about this, Gilroy refers to the African American theorist William Du Bois. According to the latter, this schizophrenia can be overcome by musical, non-discursive practice, when an external cultural form is used to express something of one’s own. For example, the Tuvan group “Yat-Ha” played hard rock and blues in the late 1980s and early 1990s; nevertheless, it was very Tuvan music: through a countercultural statement, the musicians managed to regain their “Tuvinness”, which was greatly reduced by Soviet cultural practices .

In the colonies, especially English ones, slaves were forbidden to communicate verbally: the colonialists were afraid that there would be a rebellion. Often the way out of this situation was to convey some message through singing and music. This is how the gesture of silence, the encryption of the message, appeared in black culture. Hence the contradiction, which is especially pronounced in Afro-Caribbean styles: outwardly the music may seem cheerful and cheerful, but deep down it carries tragic content or even contains political statements that are not read by an outside observer.

IDENTITY

IDENTITY

(from the English identity - identity) is a multi-valued everyday and general scientific term that expresses the idea of constancy, identity, continuity of the individual and his self-awareness.

In the human sciences, the concept of identity has three main modalities. Psychophysiological identity

denotes the unity and continuity of the physiological and mental processes and properties of the body, thanks to which it distinguishes its cells from others, which is clearly manifested in immunology.

Social identity

is the experience and awareness of one’s belonging to certain social groups and communities.

Identification with certain social communities transforms a person from a biological individual into a social individual and personality, allowing him to evaluate his social connections and belongings in terms of “We” and “They”. Personal identity

or self-identity (Self-identity) is the unity and continuity of life activity, goals, motives and meaning in life of an individual who perceives himself as a subject of activity.

This is not some special trait or set of traits that an individual possesses, but his selfhood, reflected in terms of his own biography. It is revealed not so much in the behavior of the subject and the reactions of other people to him, but in his ability to maintain and continue a certain narrative, the history of his own Self, which maintains its integrity despite changes in its individual components. Also on topic:

PSYCHOLOGY

The concept of identity originally appeared in psychiatry in the context of studying the phenomenon of “identity crisis,” which described the state of mental patients who have lost their understanding of themselves and the sequence of events in their lives. American psychoanalyst Erik Erikson transferred it to developmental psychology, showing that identity crisis is a normal phenomenon of human development. During adolescence, every person in one way or another experiences a crisis associated with the need for self-determination, in the form of a whole series of social and personal choices and identifications. If a young man fails to resolve these problems in a timely manner, he develops an inadequate identity. Diffuse, blurred identity -

a state when an individual has not yet made a responsible choice, for example, a profession or worldview, which makes his self-image vague and uncertain.

Unpaid identity is

a state when a young man has accepted a certain identity, having bypassed the complex and painful process of self-analysis, he is already included in the system of adult relationships, but this choice was not made consciously, but under influence from the outside or according to ready-made standards.

Deferred identity

, or identification moratorium, is a state when an individual is directly in the process of professional and ideological self-determination, but postpones making a final decision until later.

Achieved identity

is a state when a person has already found himself and entered a period of practical self-realization.

Erikson's theory has become widespread in developmental psychology. Behind different types of identity are not only individual characteristics, but also certain stages of personality development. However, this theory rather describes normative ideas about how the development process should proceed; the psychological reality is much richer and more diverse. “Identity crisis” is not only and not so much an age-related phenomenon as a socio-historical phenomenon. The severity of its experience depends both on the individual characteristics of the subject, and on the pace of social renewal and on the value that a given culture attaches to individuality.

Also on topic:

PERSONALITY

In the Middle Ages, the pace of social development was slow, and the individual did not perceive himself as autonomous from his community. Unambiguously tying the individual to his family and class, feudal society strictly regulated the framework of individual self-determination: the young man did not choose his occupation, his worldview, or even his wife; others, his elders, did this for him. In modern times, the developed social division of labor and increased social mobility have expanded the scope of individual choice; a person becomes something not automatically, but as a result of his own efforts. This complicates the processes of self-knowledge. For medieval man, “knowing yourself” meant first of all “knowing your place”; the hierarchy of individual abilities and capabilities coincides here with the social hierarchy. The presumption of human equality and the possibility of changing one's social status brings to the fore the task of knowing one's internal potential capabilities. Self-knowledge turns out to be a prerequisite and component of identification .

The expansion of the sphere of the individual, special, only one’s own is well reflected in the history of the European novel. Hero of the novel of wanderings

still entirely enclosed in his actions, the scale of his personality is measured by the scale of his deeds.

In a novel of trials,

the main advantage of the hero is his preservation of his original qualities, the strength of his identity.

The biographical novel

individualizes the hero’s life path, but his inner world still remains unchanged.

In the novel of education

(18th – early 19th centuries) the formation of the hero’s identity can also be traced;

the events of his life are presented here as they are perceived by the hero, from the point of view of the influence they had on his inner world. Finally, in a psychological novel

of the 19th century. the hero’s inner world and dialogue with himself acquires independent value and sometimes becomes more important than his actions.

A change in ideological perspective also means the emergence of new questions. A person chooses not only social roles and identities. He contains within himself many different possibilities and must decide which one to prefer and recognize as genuine. “Most people, like Leibniz's possible worlds, are just equal contenders for existence. How few there are who actually exist,” wrote the German philosopher Friedrich Schlegel. But self-realization does not depend only on the “I”. Romantics of the early 19th century. complain about the alienating, depersonalizing influence of society, forcing a person to abandon his most valuable potentialities in favor of less valuable ones. They introduce a whole series of oppositions into personality theory: spirit and character, face and mask, man and his “double.”

The complexity of the problem of identity is well revealed in the dialectic of “I” and mask. Its starting point is a complete, absolute distinction: the mask is not “I”, but something that has nothing to do with me. A mask is put on to hide, to gain anonymity, to appropriate someone else's, not one's own appearance. The mask frees one from considerations of prestige, social conventions and the obligation to meet the expectations of others. Masquerade - freedom, fun, spontaneity. The mask is supposed to be as easy to take off as it is to put on. However, the difference between external and internal is relative. The “imposed” style of behavior is fixed and becomes habitual. The hero of the famous pantomime Marcel Marceau instantly changes one mask after another in front of the public. He's having fun. But suddenly the farce becomes a tragedy: the mask has grown to the face. The man writhes, makes incredible efforts, but in vain: the mask does not come off, it replaced the face, became his new face!

Thus, self-identity becomes fragmented and multiple. This is also assessed differently. In psychology and psychiatry of the 19th – early 20th centuries. constancy and stability were considered the highest values; variability and multiplicity of the “I” were interpreted as misfortune and illness, such as split personality in schizophrenia. However, many philosophical schools of the East saw things differently. Western thinkers are gradually adopting this view. The German writer Hermann Hesse wrote that personality is “the prison in which you are sitting,” and the idea of the unity of the “I” is “a fallacy of science,” valuable “only because it simplifies the work of teachers and educators in the public service and saves them them from the need to think and experiment.” “ Any “I”, even the most naive, is not unity, but a multi-complex world, this small starry sky, a chaos of forms, stages and states, heredity and possibilities

"

People try to isolate themselves from the world, withdrawing into their own “I”, but on the contrary, they need to be able to dissolve, to throw off the shell. “ ...Desperately holding on to your “I”, desperately clinging to life - this means taking the surest path to eternal death, while the ability to die, throw off the shell, forever sacrifice your “I” for the sake of change leads to immortality

"(G. Hesse. Selected , M., 1977)

.

At the end of the 20th century. these ideas spread to sociology. The image of the “Proteus man” drawn by the American orientalist and psychiatrist R.D. Lifton gained wide popularity. The traditional sense of stability and immutability of the “I,” according to Lifton, was based on the relative stability of the social structure and those symbols in which the individual comprehended his existence. At the end of the 1960s, the situation changed radically. On the one hand, the feeling of historical or psychohistorical disunity, a break in continuity with traditional foundations and values, has intensified. On the other hand, many new cultural symbols have appeared that, with the help of mass communication, easily overcome national boundaries, allowing each individual to feel a connection not only with his neighbors, but with the rest of humanity. Under these conditions, the individual can no longer feel like an autonomous, closed monad. He is much closer to the image of the ancient Greek deity Proteus, who constantly changed his appearance, becoming now a bear, now a lion, now a dragon, now fire, now water, and could retain his natural appearance of a sleepy old man only when captured and chained. The Protean lifestyle is an endless series of experiments and innovations, each of which can easily be abandoned for the sake of new psychological searches.

At the beginning of the 21st century. The gigantic acceleration of technological and social renewal, experienced as an increase in general instability, has made these problems even more pressing. As English sociologists Anthony Giddens and Zygmunt Bauman note, modern society is characterized not by the replacement of some traditions and habits with others that are equally stable, reliable and rational, but by a state of constant doubt, a plurality of sources of knowledge, which makes the self more changeable and requiring constant reflection. In a rapidly changing society, instability and plasticity of social and personal identity become natural and natural. As Bauman notes, a characteristic feature of modern consciousness is the advent of a new “short-term” mentality to replace the “long-term” one. Young Americans with a high school education will experience at least 11 job changes during their working lives. In relation to the labor market, the slogan of the day has become flexibility, “plasticity”. Spatial mobility has increased sharply. Interpersonal relationships, even the most intimate ones, have also become more fluid. No one is surprised anymore by short-term marriages or living together with a boyfriend/girlfriend without registering the marriage, etc. What we are accustomed to consider an “identity crisis” is not so much a disease as a normal state of the individual, who is forced by dynamic social processes to constantly “monitor” changes in their social position and status, ethnonational, family and civic self-determinations. The conditional, playful, “performative” nature of identifications extends even to such seemingly absolute identities as sex and gender (the problem of gender reassignment, sexual orientation, etc.). This significantly complicates the understanding of the relationship between normality and pathology. For example, gender identity disorder is a severe mental disorder, but a person who believes that all masculine and feminine properties are absolutely different and are given once and for all will also experience difficulties.

If in modern times the problem of identity came down to building and then protecting and maintaining one’s own integrity, then in the modern world it is no less important to avoid a stable fixation on any one identity and maintain freedom of choice and openness to new experiences. As the great Russian historian V.O. Klyuchevsky noted, “firmness of conviction is more often the inertia of thought than the consistency of thinking” (Klyuchevsky. Letters. Diaries. Aphorisms and thoughts about history

, M., 1968). But if earlier psychological rigidity (rigidity) often helped social survival, now it often harms it. Self-identity is increasingly perceived today not as some kind of solid, once and for all formed given, but as an unfinished developing project (E. Giddens). In the conditions of a rapidly changing society and increasing life expectancy, a person simply cannot help but renew himself, and this is not a disaster, but a natural social process, which corresponds to a new philosophy of time and life itself.

These global shifts are also taking place in Russia, but here they are much more difficult. For many years, Soviet society and culture focused not on renewal and change, but on maintaining stability, order and continuity. Every innovation seemed suspicious and potentially dangerous; the very word “modernism” was dirty. A “secure bright future” - the main advantage of socialism over capitalism - looked like a simple continuation and repetition of the present and the past. Equally strong was the alignment not with individual self-realization, but with institutionalized, rigid, bureaucratic social identities. Soviet propaganda identified society and the state, and almost all social identities of Soviet people were statist. This atmosphere was detrimental to individual initiative and creativity, but people became accustomed to this lifestyle.

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the contradictions of the emergence of a market economy caused an acute crisis of identity in the country, the questions “Who are we?” and “Where are we going? "have become urgent. If in the West the difficulties of identification are caused by pluralism and individualization, then in Russia the crisis of identity is primarily the result of the collapse of the usual society, which left a gaping void in the minds of many people. It is difficult to adapt to rapidly changing social conditions not only objectively, but also psychologically. In the early 1990s, answering the question “Who am I?” posed by sociologists, people often answered: “I’m nobody,” “I’m a cog,” “I’m a pawn,” “I’m a useless person,” “I’m a workhorse.” This feeling is especially typical for pensioners, the poor, people who feel lost, powerless and alien in this world.

To get out of this painful state and restore damaged self-esteem, many people resort to negative identification, self-affirmation by contradiction. Negative identity is constructed primarily by the image of the enemy, when the whole world is divided into “us” and “not-ours”, and all one’s own troubles and failures are portrayed as the result of the machinations of external and internal enemies. The ideology of a besieged fortress, which the Soviet government cultivated for years, takes on a distinctly nationalistic character, ethnic identifications dominate over civilian ones, and national values themselves are associated primarily with an idealized historical past (traditionalism). To the question of sociologists, “What is the first thing you associate with the thought of your people?” Many Russians put first “our past, our history” or their small homeland, “the place where I was born and raised.” A negative identity is consonant with the worldview of old people for whom active life is almost over, but it does not suit young people, whose creation is much more focused on the values of personal success and self-realization. The question of the relationship between personal and social identity and what values a specific group “We” is based on is very important both for individual self-determination and for social pedagogy.

Igor Kon