What is motive

Motive

- this is a process that controls human behavior, contributing to its organization, direction, activity and stability. It is also believed that a motive is a certain generalized image of material or ideal objects that are valuable to an individual.

Achieving these objects is the meaning of his activity for him. To a person, a motive is presented in the form of special experiences that can be both positive (when expecting to achieve these objects) and negative (when realizing the incompleteness of one’s position, the lack of this object). Schopenhauer was the first to use the concept of “motivation” in psychology.

Nowadays, the word “motivation” in psychology is understood in different ways. Some researchers believe that this is a set of processes responsible for motivation and activity; while others believe that it is a purely mental phenomenon, representing a collection of motives.

What is motivation in psychology in essence? This concept is used where they talk about achieving a certain goal and specific ways to achieve this. It is known that the same goal can be achieved in different ways. So, if a person wants to become rich, then he can get a job in a prestigious company, open his own business, write a good book, engage in criminal activity... And vice versa - the same action can be performed for different purposes. In addition, the desire to achieve a specific goal can also be explained by one’s own considerations. Why does a person want to get rich? Someone wants to buy a mansion by the sea, someone wants to get married, someone wants to professionally do what they love (and not something that just generates income). In such cases, they say that a person is guided by certain motives.

Usually, a person organizing some kind of activity and achieving a certain goal is guided by several motives at once, which is why psychologists talk about one or another motivation. The problem of motivation in psychology is one of the most difficult. Often a person himself does not realize exactly what motives he was guided by when he performed some actions. There are hidden motives associated with some memories, fears, etc. Such motives are not reflected in consciousness and act on a subconscious level; a person only feels some kind of vague tension, discomfort, which he strives to overcome with the help of certain actions.

Thus, a goal is what we want to achieve, and a motive is the reason why we want to achieve it. Motivation in psychology is understood as both the set of motives that control an individual’s behavior and the process of this control itself.

Needs and motivation of personality behavior

Modern psychology believes that the source of personality activity is needs. It is they who direct the individual to master specific values and thereby act as life programs.

Needs act as a reflection in the consciousness of the individual of a certain need, a need for something. They depend on specific living conditions. Satisfaction or dissatisfaction with living conditions gives rise to certain needs that encourage the individual to take active action aimed at satisfying the need that has arisen. However, activity arises not only because a person is in need, but also because he needs to create something. Therefore, the need acts as a certain program of life activity. Needs are the force that ensures self-preservation, self-development and activity of the individual. All human needs are determined by the process of his historical development. Typically, the following groups of needs are distinguished: depending on their origin, they are divided into natural and cultural. Natural ones underlie human life (these are the needs for food, clothing, housing, etc.). They were formed in the process of socio-historical development of man. The way of satisfying many natural needs is inherited, but in the process of life they change and acquire a purely human character.

Cultural needs largely determine the general level of a person’s culture. According to the nature of the subject, they can be material, social and spiritual.

Material needs ensure the existence of the individual.

Social needs include such aspects as the need to belong to a social group and occupy a certain place in it, in the recognition of others, in communication.

Spiritual needs are specifically human needs. These include the needs for cognition and aesthetic pleasure.

Each of these groups of needs causes corresponding types of activity - material (production), social and spiritual.

A particularly important role in personality development (in addition to biological needs) is played by the need for social contacts or communication and the cognitive need.

Initially, the need for communication manifests itself in the need for contact with the mother, then it is directed to a wider circle of adults and peers. Then this need is transformed into a desire to win respect among peers. There is a need for a friend, a loved one. Even later, the desire to find a place in life, to gain public recognition, etc. arises.

Another need, which does not belong to organic needs and also appears very early, is a cognitive need. Its basis is the need for impressions, which initially manifests itself in reactions to the novelty of a stimulus. The next level is the need for knowledge (curiosity). It is expressed in interest in the subject, a tendency to study it. At the highest level, cognitive need has the character of purposeful activity. It also differs in the breadth and depth of knowledge, and in the intensity of cognitive activity.

Both of these needs are necessary for the formation of personality at all stages of its development. They are necessary just like organic needs.

Needs are characterized by some common features: firstly, each need has its own subject, i.e. it always manifests itself in something (food, clothing, a book). Needs also differ in the strength of their occurrence. Secondly, every need acquires a specific content depending on the method of satisfaction, and thirdly, needs can be reproduced; many are characterized by periodic occurrence. At the same time, they are enriched in their content. The emergence of new needs is a prerequisite for the development of personality, the driving force of its mental development. They largely depend on the general cultural level of personality development. The content of human needs is determined by the general development of the individual and the conditions in which he lives. In this way, human needs are fundamentally different from the needs of animals, in which biological need acts as the main stimulus for activity.

A. Maslow put forward a unique interpretation of the problem of needs [9, p. 35-37].

A. Maslow believed that a person’s needs are “given” and hierarchically organized by levels. If this hierarchy is presented in the form of a pyramid, then the following levels are distinguished.

1. Physiological needs (food, air, water, etc.).

2. Needs related to safety (confidence, structure, order, predictability of the environment).

3.Needs related to love (for affective relationships with others, for involvement in a group, for loving and being loved).

4. Needs related to the respect of others (competence, approval, recognition, etc.).

5.Cognitive needs (cognition, skill, research).

6. Aesthetic needs are primarily the need for beauty.

7. The need for self-actualization, manifested in the realization of one’s goals, abilities, and development of one’s own personality.

Moreover, lower-lying needs must be satisfied to some extent before a person can move on to the realization of higher ones. In general, Maslow believed that the higher a person can climb on the ladder of needs, the more individual he will be. The main stimulus that generates individual activity is, as mentioned above, needs. They manifest themselves in motives that act as direct incentives to activity.

Motive determines the type of behavior of an individual, giving it a certain direction. Along with the concept of “motive”, the term “motivation of behavior” is used. Motivation is usually understood as a set of motives that determine human behavior as a whole.

The motivational sphere of a person determines the scale and nature of his personality. A person’s motives form a hierarchical system - in some cases he may have one leading motive, in other cases there may be several motives. Typically, the hierarchical relationships of motives manifest themselves most fully in a situation of conflict, when life confronts different motives, requiring a choice to be made in favor of one of them.

Based on the same need, motives for different activities may arise. And the same activity can be caused by different motives. Thus, the motive answers the question: why does a person perform this activity? Therefore, when revealing a personality, characterizing individual actions and deeds, it is necessary to take into account the motives that led a person to certain actions.

The problem of motivation was of interest to leading Russian psychologists.

S.L. Rubinstein believed that the origins of character lie in the motives of activity. A.N. Leontiev [6, p. 206-230] considered a motive as an object that meets a particular need and believed that motives perform a dual function:

1) encourage and direct activities. These are incentive motives.

2) give the activity a subjective character, “personal meaning”. These are meaning-forming motives.

Actions are usually motivated by a system of motives. However, in terms of their role or function, not all of them, aimed at one activity, are equivalent. As a rule, one of them is the main one, the others are secondary. The main motive is usually called the leading one; other motives additionally stimulate this activity.

Every action has motives, but not every motive turns into action. Therefore, a distinction is made between realized and unrealized motives. A person may have motives for performing an action, but this does not mean that he always implements them. For example, the presence of a need for music does not at all mean that a person will do anything to satisfy it. It may also be that the object of need does not cause any orientation of the personality.

There is a distinction between the concepts of “motive” and “goal”.

A goal is a foreseen result towards which an action is directed. Motive is the drive to achieve a goal. The goal, as a rule, can be clear, but the motives are not always defined. Depending on the motive, the activity can acquire different personal meaning. With one goal, the meaning of the activity changes along with the change in motive. Personal meaning is understood as the experience of increased, subjective significance of an object, action or event that finds itself in the field of action of the leading motive (according to A.N. Leontiev).

It is possible to shift the motive to the goal and turn it into a motive. This means that a goal, previously driven to implementation by some motive, can acquire an independent motivating force, i.e. become a motive.

The basis of motivation can be different: it is a necessary reality, a sense of duty, the emotional state of the individual at the moment, and many others. etc. Moreover, all of them can manifest themselves with varying strengths, but they are always refracted through the system of our needs.

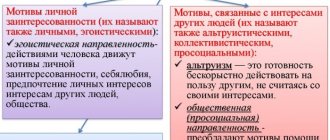

Motives are classified on various grounds. The simplest classification in relation to activity.

Motives that motivate activity that are not related to it are called external, and motives that are directly related to the activity itself are called internal. For example, the motive for learning may be associated with the desire to receive a good grade and praise, or perhaps with the desire to learn. In the first case we can talk about an external motive, in the second - about an internal one.

A.N. Leontiev, dealing specifically with the problem of motivation, pointed out that there can be understandable and actually operating motives. Moreover, it is important that the understood motive becomes really effective. (The student understands that he needs to prepare his homework, but this does not mean that he will do it.)

Thus, motives act as incentives for activity, which can be carried out at a conscious and unconscious level. As a result, all motives can be divided into two large groups: conscious and unconscious.

Conscious motives are characterized by the fact that a person is aware of what motivates him to act, what is the content of his needs. The higher the degree of awareness of the motive, the more actively the person acts. Conscious motives determine life goals that guide the activities of an individual over a long period of his life. These include interests, beliefs, and worldview of the individual.

Interests represent an individual’s emotionally charged desire to understand some object or phenomenon. Interests reveal the emotional orientation of the individual (a person is interested in what gives him satisfaction); cognitive (manifested in the desire to know), volitional (associated with the need to overcome difficulties that arise on the way to achieving goals).

There are situational, episodic and personal, persistent interests. They can be classified by content, purpose, breadth and sustainability.

In terms of content, interests are characterized by a certain orientation: material, socio-political, professional, cognitive, aesthetic, sports, etc.

The difference in interests based on goals reveals their direct and indirect nature: direct is interest in the process of activity itself, indirect is interest in the results of activity.

Interests vary in breadth; they can be concentrated in one area, or they can be distributed among many objects.

Interests are also divided according to the degree of their stability and are characterized by varying duration and preservation. The stability of interests is expressed in the duration of preservation.

Conviction as a conscious motive of behavior gives all individual activities special significance and clear direction. Beliefs are characterized by high awareness and their closest connection with the world of feelings. This is a system of stable principles.

Worldview is a conscious system of established views on the world around us and our place in it. Each person has a specific worldview that guides him in everyday life and in his practical activities.

Unconscious motives are characterized by the fact that a person is not aware of what motivates him to act, what is the content of his needs. A number of motives are not realized, but this does not mean that they are not represented in consciousness. They appear in consciousness, but in a special form. Unconscious drivers include drives, conformism, and attitudes.

Drives are expressed in the fact that a person strives to satisfy an insufficiently realized need and play a huge role in the life of an individual, since they are an internal stimulus to perform a certain action. Arising outside of a person’s consciousness, drives are closely related to conscious motives-goals, interests, etc. This connection is manifested in the fact that conscious motives are decisive in the form and direction of the realization of drives: they can slow down or suppress some drive, facilitate its transfer from one object to another, etc. Thus, unconsciousness of drives is a transitory characteristic; drives change, being formed in different types of activities under the influence of socially determined influences. Therefore, drives as unconscious impulses act as a stage in the formation of motives for human behavior.

Conformity is the subordination of the individual to group pressure, arising from the conflict between the opinions of the individual and the opinions of others. Conformity as a personality trait manifests itself in the fact that a person acts unconsciously, choosing the point of view of others. But conformism can manifest itself as a conscious adaptation of the individual to the opinion of the group, regardless of whether it corresponds or does not correspond to one’s own internal position.

The unconscious motivator of activity is the attitude. An attitude is understood as an unconscious state of a person’s readiness to perceive, evaluate and act in a certain way in relation to the people or objects around him.

“Attitude Theory” was founded by the Georgian psychologist D. Uznadze. Any behavior, in his opinion, is the implementation of specific preparedness; not a single action arises out of nowhere. Attitude is the basis for a person’s expedient selective activity. Under its influence, a person cannot always clearly explain why he acts this way and not otherwise. As a result of the research, it was found that attitudes have a great influence on the behavior of the individual, on the perception of a particular person, and on decision-making.

Psychological research has identified three substructures in the structure of an attitude: cognitive (what a person is ready to know and perceive), emotional-evaluative (a complex of likes and dislikes towards the object of an attitude), behavioral (readiness to act in a certain way in relation to the object of an attitude, to exercise volitional efforts).

Unconscious motivators of human activity, as well as conscious forms of behavior, play a fundamental role in the process of development and formation of personality.

Types of motives in psychology

Psychologists identify a large number of types of motives, dividing them into several categories. It is not easy to create such a classification, since there are a lot of circumstances that guide a person; Each direction of psychology and each school has its own system. However, the most widespread division of motives into four groups.

Internal and external motives

These types are important not only in terms of the choice of means and ways to achieve the goal, but also for the self-realization of human individuality. Internal motives are such as interests, hobbies, the need for positive emotions and avoidance of negative ones, the desire to increase self-esteem, etc. These circumstances are related to the person himself and his attitude to his activities.

External motivation is circumstances that do not depend on a person and his desires and lie outside his personal sphere. These may be motives such as public opinion, a change in weather, the desire to get a higher grade or avoid punishment, etc.

External and internal motivations can work simultaneously, or they can act separately. For example, a student diligently does his homework. He can do this both because he is interested in the topic, and in order to get a good grade, please his parents, brag to his friends, etc.

External motivation plays a fairly large role in human life, since most people need a certain socialization. Such motives are often more effective than internal ones; this is the same “kick in the ass” without which some people will not do anything at all. However, for personal development, internal motives are still the most preferable. Only with their help can you do your work truly productively. All creative activity is based primarily on internal motivation.

Positive and negative motives

Like needs, drives are associated with emotions. A person in his actions can be driven by the desire to receive pleasure, pleasure, and then this is a positive motivation, or he can also be driven by the desire to avoid punishment, pain, fear and other negative experiences, and then this is a negative motivation.

Researchers cannot yet definitively say which of these motives are more effective in achieving a goal. Negative motivation can encourage one to overcome obstacles, endure minor inconveniences, and work until exhaustion; but it also destroys a person who will never truly love or understand his business. Therefore, positive motives still seem more preferable.

Sustainable and unstable motives

Stable motivations are those that are based on human needs and do not require any additional reinforcement. Such motives have existed for quite a long time. Unsustainable motivation changes quickly. Thus, the internal motivations of the individual are stable, since changes in worldview, interests, and tastes occur rarely and gradually. External motivation, on the contrary, is unstable, since the demands of society, the mood of others, and the weather outside change quickly.

Achieving success

This is a separate type of motivation that has become relevant recently. Modern society sets a person up for success from childhood. It is not prestigious to be unsuccessful; success brings with it material well-being, public recognition, and other benefits. Success increases a person's social status.

It would seem that every person wants to achieve success. However, in reality, there are many obstacles on the way to achieving it, which sometimes discourage the desire to achieve success altogether. One of the reasons for this is a person’s lack of understanding of why he needs to achieve this goal. It happens that the set goal is too far away and gets lost among the many obstacles that arise; in this case, it is advisable to break the achievement of this success into several intermediate goals.

Often achieving great success involves leaving the so-called comfort zone. This means sacrificing something small in order to get something much bigger in the end; the ability to take risks, endure small troubles with the expectation that these problems will be more than compensated for when success is achieved. And this is where many potentially successful people give up.

Often the “comfort zone” is presented as a physical, mental, ideological or spiritual space in which a person feels good and comfortable, he does not suffer and, it would seem, is provided with everything he needs. In fact, psychologists understand something different by this concept. For some people, the “comfort zone” is associated precisely with suffering, inconvenience, pain, and leaving this zone can relieve suffering and bring happiness. But a person does not want to make this exit; he feels “good” when he feels bad. What is the reason for this paradox?

This situation is perfectly illustrated in the famous play “Dragon” by E. Schwartz, based on which a film was made in the late 80s. The inhabitants of the fairy-tale city come to terms with the fact that a terrible dragon has established dictatorial rule over them, who sets his own rules and, in particular, regularly demands that the most beautiful girls in the city be given to him. When a brave knight appears and kills the dragon and gives the inhabitants freedom, they immediately... elect a new dictator who makes them suffer in the same way. It turned out that the residents could not make an effort to learn to live without any dictators and suffering: in their minds, freedom, thinking, responsibility and hard work seem to be even greater suffering than the insane rules of this or that dictator, which one can get used to. The dragon freed people from the need to think and gave them, albeit unfair and deceitful, but a simple and understandable picture of the world, which was enough to learn by heart.

Types of Human Motivation

Such types of motivation as “carrot” and “stick” are widely known. This is nothing more than an idea of negative and positive motives. These principles have long been used in economics, politics, management, education and other areas, including everyday life.

It is interesting that these types of motivations can characterize not only an individual, but also a certain society. It is known, for example, that since ancient times the Russian consciousness has been more characterized by “stick” motivation than “carrot” motivation. This is even reflected in the proverbs: “Until thunder strikes, a man will not cross himself.” A similar character of the Russian person was noted by researchers of culture and even religion. Thus, one church historian said that Russian Orthodox people have long believed not so much in God as in the devil, and in Russian religious (and for the most part folk-religious) culture, thousands of ways and advice have arisen on how to avoid meeting with evil spirits; at the same time, original Orthodoxy condemns such a practice, because if a person believes in “an all-powerful God,” then he should not be afraid of evil spirits.

“Gingerbread” is largely a Western system of motifs. Thus, in European countries there are a number of incentives for citizens who strictly comply with the law, and a relatively mild system of punishments for those who violate the laws. In our country, the opposite is true: practically nothing is provided for law-abiding citizens, but the system of punishments is extensive, confusing, cruel and clumsy.

However, in modern Western society the role of the “stick” in certain areas is also growing. There, cruel treatment of children and violation of discipline in enterprises are severely condemned. The existing problems, say, in public health care in themselves are a “stick” for Europeans, encouraging them to work hard to pay for private medical services.

Which of these motives are most effective? Each country and each people has its own answer to this question. History shows that European society was favorably influenced by the widespread increase in the “carrot”, that is, the development of positive motives; but opposite trends led to revolutions, strikes, spontaneous and organized mass protests. This has been evident in European history for centuries.

In modern Singapore, the “whip” played a key role in the prosperity of society. There are a great many restrictions and prohibitions in this city-state, and in order to maintain impeccable order, punishments such as caning are widely used. There are no “carrots” for citizens here. And it seems strange to many of us how such methods have led Singapore to an economic and social miracle, high standards of living, social cohesion (and this in a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural country with a high population density) and the absence of mass discontent.

The countries of Eastern Europe, the USA, and China stand out in that their societies maintain a certain balance of incentives. For Eastern Europe, this was especially noticeable during the years of the Soviet bloc: citizens loyal to the state regime, who worked conscientiously and cared about their high “moral character” (from the point of view of the authorities), were guaranteed a fairly high standard of living, a certain degree of civil liberties, provision of consumer goods. And next to this is the brutal persecution of dissidents, dissidents, “parasites,” and the condemnation of an immoral way of life, elevated to ideology. Something similar could be seen in these countries both before and after the “Soviet era.” Only people who were characterized by a struggle between opposing systems of motives could build such a society. To compare this with the Western European system, just look at the prisons in these countries: Norwegian or Dutch ones are more reminiscent of resort hotels, and Polish or Romanian ones are more like a concentration camp.

This makes some sense. In the cultures of different countries, the image of a prison is given the role of a kind of “scarecrow”, with the help of which some people try to motivate others, thereby controlling their behavior. In Russia, the USA, China and the countries of Eastern Europe, a prison is not a correctional institution, but an “institution for the execution of punishments,” and its task is to oppress and destroy the individual, to destroy the criminal morally and often physically. And only the desire not to “slide” to the point of ending up behind bars gives the average person in these countries the impetus to perform socially useful actions (work, provide for their family, respect others, do not steal, do not kill, etc.). The first opportunity to avoid a prison sentence motivates a typical resident of these countries to commit a crime.

The behavior of Europeans is subject to different principles. Apparently, a prison term does not frighten them: after all, the existing restrictions in the prisons there do not humiliate the prisoner as an individual, the prison staff show him a certain respect. But at the same time, the discipline of Europeans, their politeness, and desire to work hard (but not overwork) is amazing. If you leave a wallet with money on a bench in some German city, then, most likely, a week later you will find it there completely untouched (currently the situation is much different due to the abundance of migrants in Germany and other European countries who have completely different psyche). The reason is that the average European is determined to achieve success and maintain his good reputation, and any “wrong” action can ruin this reputation. You won’t go to jail, but your friends will turn away from you, your girlfriend will stop loving you, your parents will kick you out of the house, you won’t be hired by a good organization...

If you delve into history, you can see what motivated people in different countries, creating similar inventions, performing the same actions. A good example is the creation of a printing press. Johannes Gutenberg was definitely positively motivated: with the help of his printing house, he wanted to improve his financial condition, gain fame and influence, become a pioneer of something new, and give people new opportunities for development. He was the creator, chief worker and owner of his enterprise. In fact, he succeeded in his plans: not only merchants and artisans, but also royalty and the church became his clients.

The Russian pioneer printer Ivan Fedorov was motivated by slightly different considerations. For him, his work was rather ritual; he wanted to “serve God.” The visible analogues of “god” for him were rulers, church hierarchs, and boyars. In the first Moscow printing house, opened by the Tsar and Metropolitan for personal needs, Fedorov was a powerless worker, and he did not want to have any personal benefits from this enterprise. For a long time, the pioneer printer was driven by circumstances that did not allow him to fully implement his plans: ordinary priests and book copyists were angry with him, the printing house was quickly burned and forced him to flee the country to Lithuania, and then to Ukraine. Outside Russia, the pioneer printer's business went much better, but again at the expense of strong rulers. The Russian pioneer printer never acquired his own personal printing house. Apparently, the Christian god and government officials were for Fedorov a kind of “whip” that should be feared and served.

“The Man in the Case” is another character, now literary, who was clearly motivated solely by the “whip”. His favorite saying was the expression “no matter what happens,” which he repeated whenever he saw something unusual. Those around him were surprised where this petty official, a quiet and inconspicuous man, suddenly awakened with remarkable energy, with which he began to scribble complaints left and right. All-encompassing fear prompted him to act, while those around him were motivated in their actions by positive considerations.

Motivation according to Maslow

The problem of personal motivation was actively studied by Abraham Maslow. In his works, he argued that man is a creature who always wants something. If he satisfies one of his needs, then after that he will want to satisfy another. And you can notice this in other people (if you don’t notice this in yourself).

A striking example is the constantly unabating whims of a woman. First, they want to find at least some men with whom they can build relationships. Then they become dissatisfied with the qualities of the men who appear, whom they begin to remake. Then various whims of “I want” and “give” arise when a man becomes ideal.

Having satisfied one desire, a person moves on to satisfy another goal. Moreover, first a person must satisfy the needs of his body, then - desires associated with overall self-satisfaction, and then - the goals that a person consciously sets in order to somehow improve his life.

For example, a person will not think about love if his life is threatened. Also, he will not be able to think well of people if he hates them.

A. Maslow created a pyramid that clearly shows what needs a person satisfies first in order to be able to move to the next level. If the needs of the first levels are not satisfied, then the person will not be able to achieve the goal at the next levels (he will have to satisfy the primary desires first).

- Physiological needs come first: protection, satisfying hunger and thirst, sex, reproduction, etc.

- In second place, a person directs all his efforts to providing himself with protection: a home, getting rid of fears, eliminating failures, etc.

- At the third level, a person thinks about his place in society and the need for love.

- At the fourth level, a person directs all his efforts to receive approval, respect, recognition, and achieve success.

- At the fifth level, a person can expand his horizons with new knowledge, research, skills, and training.

- At the sixth level, an individual can already think about the aesthetic components of his life: beauty, harmony, order.

- At the seventh level, a person can finally improve himself, develop his personality, set new good goals, etc.

The multiplicity of needs and desires leads to the fact that a person can perform certain actions that indirectly satisfy some of his desires. For example, an individual may eat not only because of hunger, but also to improve his mood. And some people engage in sex to gain power over others, to gain sympathy, to feel needed.

go to top

The struggle of motives

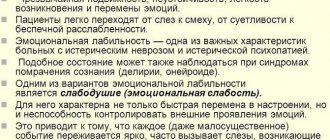

As already mentioned, a person is simultaneously driven by many different motives. And not all of them are equivalent and equally directed. Here's a classic example. A person sets an alarm clock at night, intending to get up early the next morning - for example, to go for a morning run. But the morning comes, the alarm clock rings, and this person no longer wants to get up. He finds himself in a situation where he needs to make a specific decision, and it depends on what motives prevail in him at the moment. Here we come across what is called willpower.

This example is not particularly critical, but there are situations in life when a person has to make very difficult choices. Any of the options for action is motivated in a certain way, and this brings discomfort and even real torment. So, in some cases we are faced with a choice - to save ourselves from trouble or to save our loved ones at the cost of our own lives. Such internal conflicts can lead to the development of depression or neurosis.

What should you do if you need to make such a choice? Experts advise not to give in to emotions and carefully consider all options if possible. There must be a rational approach here; you need to weigh all the pros and cons, the benefits and deprivations that the choice you make will bring. And above all, one should be guided by socially significant motives. After all, it often happens that we achieve our goal by “walking over our heads,” as a result of which friends, close people, and relatives turn away from us, as a result, we lose more than we gain.

A person is not aware of all his motives, but control of his motivational sphere is available to us. It is necessary to create a hierarchy of needs and motivations for yourself and focus on the most significant and important of them. Such a hierarchy will be associated primarily with social values.

The “pyramid of needs” compiled by the American psychologist Abraham Maslow is widely known. This system distributes needs into “lower” ones, which make humans related to other animals, and “higher” ones, which are unique to humans. It is curious that the lower needs are associated with the individual survival of the organism, while the higher ones pursue social goals. The highest needs are the need to understand one’s connection with the entire universe, and not just with one’s small group or human society in general.

Having certain needs, a person acquires the motivations associated with them. And they motivate him to do certain things. It happens that an activity seems “higher”, but in reality a person is guided by “lower” motives. So, a musician can create fashionable but primitive music just to feed himself (and generally make money). It happens that “for bread” people create real masterpieces. In other cases, setting “lower” goals is only an intermediate step, while in reality the person is motivated by higher considerations. Thus, the father of the family can take care of his health in order to have the strength to provide for his wife and children.