Psychological foundations of activity and personality

The main condition for the harmonious development of personality is activity.

In the most general understanding of the word, activity means an individual’s focus on some kind of activity, both internal and physical. The uniqueness of the human psyche lies, first of all, in the ability to implement one’s actions in the head, which is a distinctive psychological feature. The psychological foundations of activity arise in childhood, when the child first learns to perform an action, and then is able to perform the same operation in his mind, while new abilities are gradually added, transforming objective activity into internal activity. As a result of this feature of the psyche, a person can use both his own knowledge and the experience of past generations of people. If we talk about the structure of human activity, the main elements here are:

- Goal is a conscious desire to achieve the final result;

- Motives - explain the reasons why a person wants to achieve a certain goal, which encourages a person to move according to the intended plan;

- Action implies the systematic implementation of current tasks that arise in the process of achieving the intended goal.

A change in the structure of the activity of an object image in the human psyche indicates a lack of conscious activity, i.e. the personality acts guided only by instincts, in this case they speak of the impulsive behavior of the individual.

Types of personal activities

Personality very often appears in life as a product of social relations.

At the same time, a person simultaneously acts both as a subject (active individual) and as an object (passive personality) of relationships with society, regardless of the type of activity. Communication in a social group leads to the interaction of individuals, they begin to influence each other, a common opinion appears, and a social attitude develops. The psychological characteristics of such communication between people indicate certain types of activity, as a rule, this is either a motivational sphere or a professional one.

In psychology, the main types of personality activity are distinguished:

- labor – the creation of a socially useful material good;

- creativity - the production of a completely new original product for the benefit of humanity;

- study – acquisition of various knowledge and skills for subsequent useful application in the professional field;

- a gaming type of activity is associated with knowledge of the surrounding world through any game forms, including in virtual space.

If we directly correlate the activity of an individual with age, it becomes clear that in infancy the child is engaged in a playful form of activity, in a young age – educational, and subsequently develops as a professional.

It is clear that a person is able to combine several types of activities simultaneously or alternately. Scientists have long noticed that the psychological characteristics of temperament and the characteristics of an individual’s professional activity must be combined with each other. If work does not provide moral and ethical satisfaction, then the production of material goods decreases, a person does not feel in his place, the search for himself begins, and the incentive for active work decreases. Which leads to the conclusion that not every work activity develops the personality; it is necessary to find a job that will affect the full potential of the individual.

If we briefly summarize the topic of personality and human activity, we can see that any activity of an individual develops skills. The absence of any activity leads to a gradual decline in mental functions, and personality degradation begins. For example, people who have not worked at a professional level for a long time lose skills and have to replenish their knowledge through training. Depriving an individual of his favorite activity leads to a loss of meaning in his own existence and to depression.

- 3.1. Psychological theory of activity

Topic 3. Personality and activity

3.1. Psychological theory of activity

Basic concepts and principles.

The psychological theory of activity was created in Soviet psychology and has been developing for more than 50 years. It is comprehensively disclosed in the works of domestic psychologists - L.S. Vygotsky, S.L. Rubinshteina, A.N. Leontyeva, A.R. Luria, A.V. Zaporozhets, P.Ya. Galperin and many others. The psychological theory of activity began to be developed in the 1920s – early 1930s. By this time, the psychology of consciousness had already faded into the background and new foreign theories were in bloom - behaviorism, psychoanalysis, Gestalt psychology and a number of others. Thus, Soviet psychologists could already take into account the positive aspects and disadvantages of each of these theories.

But the main thing was that the authors of the theory of activity adopted the philosophy of dialectical materialism - the theory of K. Marx, and above all its main thesis for psychology that it is not a person’s consciousness that determines his being and activity, but on the contrary, being and activity determine consciousness. This general philosophical thesis found a concrete psychological development in the theory of activity.

The theory of activity is most fully presented in the works of A.N. Leontiev, in particular in his latest book “Activity. Consciousness. Personality." We will stick mainly to his version of this theory.

Ideas about the structure, or macrostructure, of activity, although they do not completely exhaust the theory of activity, form its basis. Human activity has a complex hierarchical structure. It consists of several layers, or levels. Let's name these levels, moving from top to bottom:

• level of special activities (or special types of activities) (for more details on this, see p. 79);

• level of action;

• level of operations;

• level of psychophysiological functions.

Operational and technical aspects of activity.

Action is the basic unit of activity analysis.

By definition, an action

is a process aimed at realizing the goal of an activity. Thus, the definition of action includes another concept that needs to be defined - goal.

What is a goal?

This is an image of the desired result, i.e. the result that should be achieved during the execution of the action.

Note that here we mean conscious

the image of the result: the latter is retained in consciousness the entire time the action is carried out, therefore it makes no sense to talk about a “conscious goal”: the goal is always conscious. Is it possible to do something without imagining the end result? Of course you can. For example, wandering aimlessly through the streets, a person may find himself in an unfamiliar part of the city. He is not aware of how and where he got to, which means that in his mind there was no final point of movement, i.e., a goal. However, a person’s aimless activity is more an artifact of his life activity than a typical phenomenon.

Characterizing the concept of “action”, we can highlight the following four points.

1. Action includes, as a necessary component, an act of consciousness in the form of setting and maintaining a goal. But this act of consciousness is not closed in itself, as the psychology of consciousness actually asserted, but is revealed in action.

2. Action is at the same time an act of behavior. Consequently, the theory of activity also preserves the achievements of behaviorism, considering the external activity of animals and humans as an object of study. However, unlike behaviorism, it considers external movements in inextricable unity with consciousness, because movement without a goal is more likely a failed behavior than its true essence.

So, the first two points consist in recognizing the inextricable unity of consciousness and behavior. This unity is already contained in the main unit of analysis - action.

3. Through the concept of action, activity theory affirms the principle of activity,

contrasting it with the principle of reactivity. These two principles differ in where, in accordance with each of them, the starting point of activity analysis should be placed: in the external environment or inside the organism (subject). For J. Watson, the main thing was the concept of reaction. Reaction (from Latin re... - against + actio - action) is a response action. The active, initiating principle here belongs to the stimulus. Watson believed that all human behavior could be described through a system of reactions, but the facts showed that many behavioral acts, or actions, cannot be explained based solely on an analysis of external conditions (stimuli). It is too typical for a person to act in a way that obeys not the logic of external influences, but the logic of his internal goal. These are not so much reactions to external stimuli as actions aimed at achieving a goal, taking into account external conditions. Here it is appropriate to recall the words of K. Marx that for a person, a goal as a law determines the method and nature of his actions. So, through the concept of action, which presupposes an active principle in the subject (in the form of a goal), the psychological theory of activity affirms the principle of activity.

4. The concept of action “brings” human activity into the objective and social world. The presented result (goal) of an action can be anything, and not only and not even so much biological, such as, for example, obtaining food, avoiding danger, etc. This can be the production of some material product, establishing social contact, gaining knowledge and etc.

Thus, the concept of action makes it possible to approach human life with scientific analysis precisely from the aspect of its human specificity. Such a possibility could not be provided by the concept of reaction, especially innate, from which J. Watson proceeded. Man, through the prism of Watson’s system, acted primarily as a biological being.

The concept of action reflects the main starting points, or principles,

theories of activity, the essence of which is as follows:

1) consciousness cannot be considered as closed in itself: it must be brought into the activity of the subject (“opening” the circle of consciousness);

2) behavior cannot be considered in isolation from a person’s consciousness. When considering behavior, consciousness must not only be preserved, but also defined in its fundamental function (the principle of the unity of consciousness and behavior);

3) activity is an active, purposeful process (the principle of activity);

4) human actions are objective; they realize social – production and cultural – goals (the principle of the objectivity of human activity and the principle of its social conditionality).

The next, lower level in relation to action are operations. Operation

called the method of performing an action. A few simple examples will help illustrate this concept.

1. You can multiply two two-digit numbers both mentally and in writing, solving the example “in a column.” These are two different ways of performing the same arithmetic operation, or two different operations.

2. The “female” way of threading a needle is that the thread is pushed into the eye of the needle, while men push the eye onto the thread. This is also a different operation, in this case motor.

3. To find a specific place in a book, they usually use a bookmark. But, if the bookmark falls out, you have to resort to another way of finding the required paragraph: either try to remember the page number, or, while flipping through the book, skim each page with your eyes, etc. There are again several different ways to achieve the same goal.

Operations characterize the technical side of performing actions, and what is called “technique,” dexterity, dexterity, refers almost exclusively to the level of operation. The nature of the operations performed depends on the conditions under which the action is performed. In this case, conditions mean both external circumstances and the possibilities, or internal means, of the acting subject himself.

Speaking about the psychological characteristics of operations, it should be noted that their main property is that they are little realized or not realized at all. In this way, operations are fundamentally different from actions that presuppose both a conscious goal and conscious control over their progress. Essentially, the operations level is filled with automatic actions and skills. The characteristics of the latter are at the same time the characteristics of the operation.

So, according to activity theory:

1) operations are of two kinds: some arise through adaptation, adaptation, direct imitation; others - from actions by automating them;

2) operations of the first kind are practically not realized and cannot be evoked in consciousness even with special efforts. Operations of the second kind are on the border of consciousness and can easily become actually conscious;

3) every complex action consists of actions and operations.

The last, lowest level in the structure of activity consists of psychophysiological functions.

Speaking about the fact that a subject carries out an activity, we must not forget that this subject is at the same time an organism with a highly organized nervous system, developed sensory organs, a complex musculoskeletal system, etc.

Psychophysiological functions in activity theory are understood as physiological support for mental processes. These include a number of abilities of the human body: the ability to sense, to form and record traces of past influences, motor ability, etc. Accordingly, they speak of sensory, mnemonic and motor functions. This level also includes innate mechanisms fixed in the morphology of the nervous system, and those that mature during the first months of life. The boundary between automatic operations and psychophysiological functions is quite arbitrary, however, despite this, the latter are distinguished into an independent level due to their organismic nature. They are given to the subject of activity by nature; he does not have to do anything to have them, and finds them within himself ready for use.

Psychophysiological functions constitute both necessary prerequisites and means of activity. We can say that psychophysiological functions are the organic foundation of activity processes. Without relying on them, it would be impossible not only to carry out actions and operations, but also to set the tasks themselves.

Concluding the description of the three main levels in the structure of activity - actions, operations and psychophysiological functions, we note that these levels are associated with a discussion of predominantly operational and technical aspects of activity.

Motivational and personal aspects of activity.

Need is the initial form of activity of living organisms. It is best to start analyzing needs with their organic forms. In a living organism, certain states of tension periodically arise, associated with an objective lack of substances (objects) that are necessary for the continuation of the normal functioning of the body. It is these states of the organism’s objective need for something lying outside of it that constitute a necessary condition for its normal functioning and are called needs. These are the needs for food, water, oxygen, etc. When it comes to the needs with which a person is born (and not only humans, but also higher animals), then at least two more must be added to this list of elementary biological needs: social need (need for contacts) with others like oneself, and primarily with adult individuals, and the need for external impressions (cognitive need).

The subject of need is often defined as a motive. The definition of a motive as an object of need should not be taken too literally, imagining the object in the form of a thing that can be touched. The subject can be ideal, for example, an unsolved scientific problem, an artistic design, etc.

A set, or “nest,” of actions that gather around one object is a typical sign of a motive. According to another definition, motive is that for which an action is performed. “For the sake of” something, a person, as a rule, performs many different actions. This set of actions that are caused by one motive is called activity, and more specifically, special activity.

or

a special type of activity.

Playing, educational, and work activities are usually cited as examples of special types of activities. The word “activity” is attached to these forms of activity even in everyday speech. However, the same concept can be applied to a host of other human activities, such as caring for a child, playing sports, or solving a major scientific problem.

The level of activities is clearly separated from the level of actions, since the same motive can be satisfied by a set of different actions. However, the same action can be motivated by different motives.

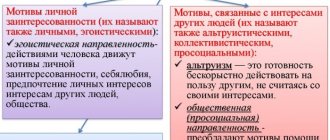

The actions of a particular subject are usually prompted by several motives at once. Multimotivation of human actions is a typical phenomenon. For example, a person can work well for the sake of a high quality result, but at the same time satisfies his other motives - social recognition, material reward, etc. In terms of their role or function, not all motives “converging” on one activity are equivalent. As a rule, one of them is the main one, the others are secondary. The main motive is called the leading one, the secondary ones are called incentive motives: they do not so much “launch” as additionally stimulate this activity.

Turning to the problem of the relationship between motives and consciousness, we note that motives give rise to actions, that is, they lead to the formation of goals, and goals, as we know, are always realized. The motives themselves are not always understood. As a result, all motives can be divided into two classes: conscious and unconscious. Examples of conscious

Motives can serve as significant life goals that guide a person’s activities over long periods of his life.

These are motives-goals. The existence of such motives is typical for mature individuals. The class of unconscious

motives is much larger, and before a person reaches a certain age, almost all motives are included in it.

The work of understanding your own motives is extremely important, but at the same time very difficult. It requires not only great intellectual and life experience, but also great courage. In essence, this is a special activity that has its own motive - the motive of self-knowledge and moral self-improvement.

Unconscious motives, like conscious ones, manifest themselves in consciousness, but in special forms. There are at least two such forms: emotions and personal meanings.

Emotions

arise only in connection with such events or results of actions that are associated with motives. If a person cares about something, then this “something” affects his motives.

In activity theory, emotions are defined as a reflection of the relationship between the result of an activity and its motive. If, from the point of view of motive, the activity is successful, positive emotions arise, if unsuccessful, negative emotions arise.

Emotions are a very important indicator that serves as a key to unraveling human motives (if the latter are not realized). You just need to notice for what reason the experience arose and what its properties were. It happens, for example, that a person who has committed an altruistic act experiences a feeling of dissatisfaction. It is not enough for him that he helped another, since his action has not yet received the expected recognition from others and this disappointed him. It was the feeling of disappointment that suggested the true and, apparently, main motive that guided him.

Another form of manifestation of motives in consciousness is personal meaning.

This is the experience of increased subjective significance of an object, action or event that finds itself in the field of action of the leading motive. It is important to emphasize here that only the leading motive acts in the meaning-forming function. Secondary motives (stimulus motives) play the role of additional incentives; they generate only emotions, but not meanings.

The phenomenon of personal meaning is clearly revealed during transition processes, when an object that was neutral until a certain moment suddenly begins to be experienced as subjectively important. For example, boring geographical information becomes important and meaningful when you plan a hike and choose a route for it. Discipline in the group begins to worry you much more if you are appointed as a prefect.

The connection between motives and personality.

It is known that human motives form a hierarchical system. If we compare the motivational sphere of a person with a building, then for different people this building will have a different shape. In some cases it will be like a pyramid with one vertex - one leading motive, in other cases there may be several vertices (i.e., meaning-forming motives). The entire building can rest on a small foundation - a narrow egoistic motive - or rest on a broad foundation of socially significant motives, which include the destinies of many people and various events in the circle of human life. Depending on the strength of the leading motive, the building can be high or low, etc. The motivational sphere of a person determines the scale and character of his personality.

Usually, the hierarchical relationships of motives are not fully realized by a person. They become clearer in situations of conflict of motives. It is not so rare that life collides different motives, requiring a person to make a choice in favor of one of them: material gain or business interests, self-preservation or honor.

Development of motives.

When analyzing activity, the only way is from need to motive, and then to goal and action [P-M-C-D (need - motive - goal - activity)]. In real activity, the reverse process constantly occurs: in the course of activity, new motives and needs are formed [D-M-P (activity - motive - need)]. It cannot be otherwise: for example, a child is born with a limited range of needs, mainly biological.

In the theory of activity, one mechanism for the formation of motives is outlined, which is called the “mechanism of shifting the motive to the goal” (another option is the “mechanism of transforming the goal into a motive”). The essence of this mechanism is that a goal, previously prompted to its implementation by some motive, over time acquires an independent motivating force, that is, it itself becomes a motive.

It is important to emphasize that the transformation of a goal into a motive can only occur with the accumulation of positive emotions: it is well known that it is impossible to instill love or interest in a business through punishment and coercion alone. An object cannot become a custom motif even with a very strong desire. He must go through a long period of accumulation of positive emotions. The latter act as a kind of bridges that connect a given object with the system of existing motives until a new motive enters this system as one of them. An example would be this situation. A student begins to willingly study a subject because he enjoys communicating with his favorite teacher. But over time, it turns out that interest in this subject has deepened, and now the student continues to study it for its own sake and, perhaps, even chooses it as his future specialty.

Internal activities.

The development of the theory of activity began with the analysis of external, practical human activity. But then the authors of the theory turned to internal activity.

What is internal activity? Let us imagine the content of that internal work, which is called mental and which a person is constantly engaged in. This work does not always represent the actual thought process, that is, the solution of intellectual or scientific problems - often during such reflections a person reproduces (as if playing out) the upcoming actions in his mind.

The function of these actions is that internal actions prepare external actions. They save a person’s efforts, giving him the opportunity, firstly, to accurately and quickly select the desired action, and secondly, to avoid gross and sometimes fatal mistakes.

In relation to these extremely important forms of activity, activity theory puts forward two main theses.

1. Similar activity is an activity that has fundamentally the same structure as external activity, and differs from it only in the form of its occurrence. In other words, internal activity, like external activity, is stimulated by motives, accompanied by emotional experiences, and has its own operational and technical composition, that is, it consists of a sequence of actions and operations that implement them. The only difference is that actions are performed not with real objects, but with their images, and instead of a real product, a mental result is obtained.

2. Internal activity arose from external, practical activity through the process of internalization, by which is meant the transfer of corresponding actions to the mental plane. Obviously, in order to successfully perform some action “in the mind”, it is necessary to master it in material terms and first obtain a real result. For example, thinking through a chess move is possible only after the real moves of the pieces have been mastered and their real consequences have been perceived.

It is equally obvious that during internalization, external activity, without changing its fundamental structure, is greatly transformed. This especially applies to its operational and technical part: individual actions or operations are reduced, and some of them are eliminated altogether; the whole process is much faster.

Can mental processes and functions be described by the concepts and means of activity theory? Is it possible to discern structural features of activity in them? It turns out that it is possible! For several decades, Soviet psychology has been developing an activity-based approach to these processes.

Table of contents